By Christopher S. Cotton & Ardyn Nordstrom

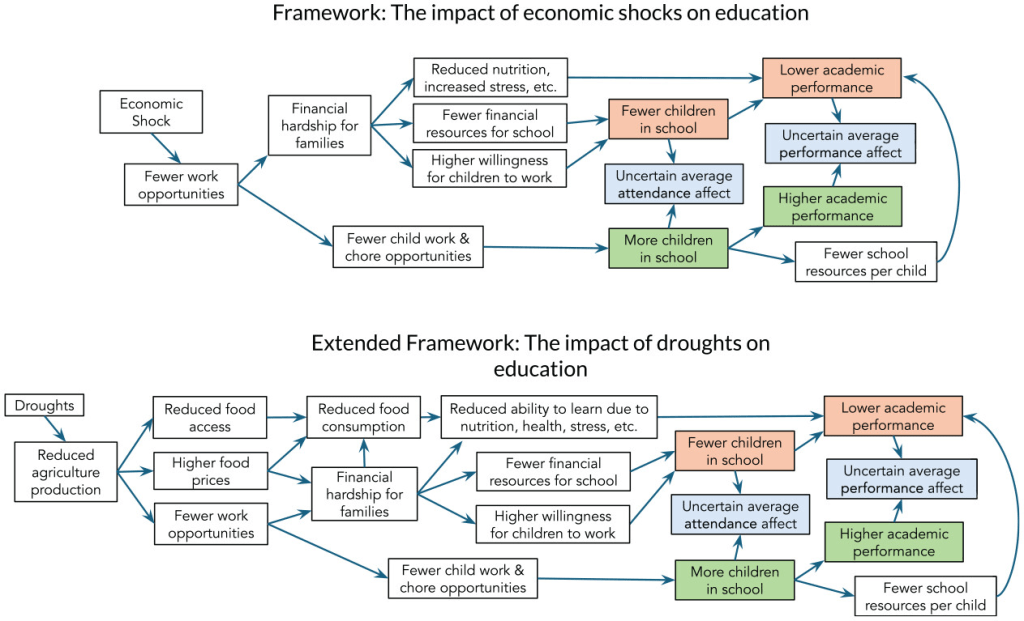

Over recent decades, global education has made significant strides. More children than ever are attending school. But how resilient are these gains during economic downturns or environmental crises?

Our recent study explored how a severe drought in rural Zimbabwe impacted education outcomes. We found that the agricultural and economic shock increased school attendance and progression, standard measures that are typically correlated with increased learning. From these results alone, we may have concluded that droughts encourage kids to attend more school, thereby increasing their education outcomes.

However, we had access to a detailed data set on test scores from the region, the analysis of which told a different story. Even as children attended school at higher rates, their performance and learning progress decreased. Crises drove kids to school, but did not increase learning.

Our findings highlight a broader challenge: the correlation between more schooling and more learning can break down during crises. Higher attendance and enrollment rates alone should not be viewed as indicators that children have better education outcomes during such times. Studies that rely on the quantity of education to assess impact may come to the wrong conclusions. This disconnect calls for rethinking how we measure education success during challenging times.

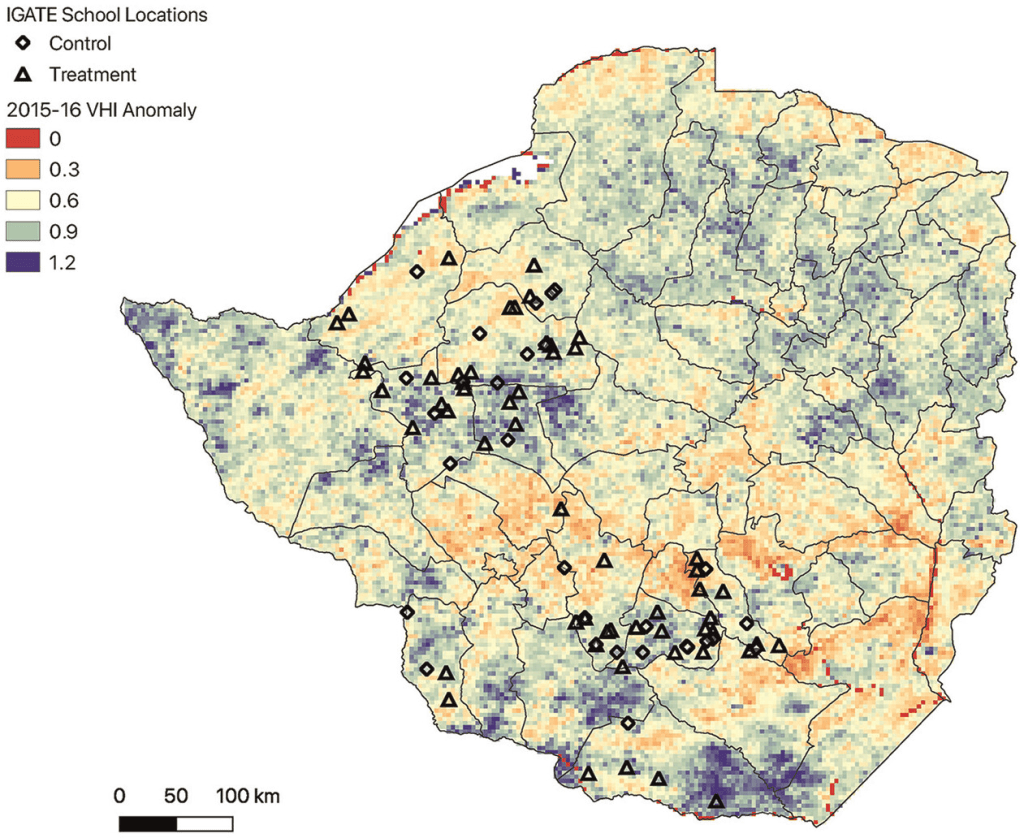

Combining Satellite Imagery with Program Data

Evaluating how crises impact education is tough. Crises can’t be randomized like controlled experiments, and collecting real-time data before they strike is rarely feasible. Our approach addresses this by linking detailed, external satellite imagery data with educational data from a project that just happened to be taking place in the region at the time.

We used the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Vegetation Health Index—a satellite measure of agricultural productivity and drought severity. By combining this data with comprehensive education information from the UK-funded Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) project in Zimbabwe, we had a powerful data set for assessing the impact of the climate shock on students.

Although our study focuses on drought, the approach can also be used to assess other shocks. In an earlier blog post, we detailed satellite imagery and the hidden potential of development program data.

Attendance Rises, Learning Does Not

Our findings reveal a surprising trend. During Zimbabwe’s severe drought in 2015–16, school attendance and grade progression went up. With fewer opportunities for agricultural labor, more children attended school regularly.

However, increased attendance did not lead to better learning outcomes. Literacy and numeracy scores remained stagnant or worsened, particularly among economically vulnerable students. Those from food-insecure households were hit hardest. This finding suggests that traditional metrics like attendance might provide an incomplete picture of educational success during crises.

Importance of Dual Measurement when Assessing Educational Success

These results highlight the need for dual measurement strategies. Simply counting attendance or enrollment risks missing critical educational shortfalls. Incorporating direct assessments of student learning, such as literacy and numeracy evaluations, is crucial. Only then can we fully understand how crises affect education.

Our analysis also highlights the potential for using data from specialized development programs to assess broader trends and impacts more generally. In this case, the IGATE program data provided a richer set of learning outcomes than were available directly through schools and governments, offering researchers an opportunity to learn about more than just the program’s impact.

Chris Cotton is the Jarislowsky-Deutsch Chair in Economic & Financial Policy at Queen’s University and the Director of the John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Economic Policy. Ardyn Nordstrom is Assistant Assistant Professor at Carleton University’s School of Public Policy and Administration.