By Christopher Cotton

Jarislowsky-Deutsch Chair in Economic & Financial Policy, Queen’s University

Director of the John Deutsch Institute for the Study of Economic Policy

Last week, I had the pleasure of presenting on the future of the Canadian economy during the 38th Annual Forecast Lunch put on by the Smith School of Business and the Kingston Economic Development Corporation. This article is Part 1 in a 2-part series summarizing my presentation. Part 2 presents five economic scenarios for uncertain times.

On the surface, the Canadian economy appears to be finding its footing. Headline inflation has largely returned to target, interest rates have moderated from their 2024 peaks, and Canada continues to report relatively high GDP growth compared to many of our G7 and OECD peers.

But these positive trends mask deep structural concerns about a country that is struggling to attract investment, retain talent, and improve its standard of living. Layered on top of these domestic challenges is an unprecedented level of economic, political, and international uncertainty, making sustainable growth elusive.

The Productivity Gap: A Canadian Crisis

The disconnect between headline growth and individual prosperity is stark. While the aggregate size of the Canadian economy is expanding, it is driven by population growth rather than productivity.

As Figure 1 shows, Canada had the second-highest real GDP growth rate in the G7 over the past decade. On the surface, this sounds like a remarkable success story. But, it is actually close to meaningless. During the same period, Canada had the highest population growth rate among the G7. More workers can boost GDP, even as individual real wages are falling. That’s what we see in the other graphs in Figure 1.

Per person, Canada’s GDP has not increased over the last 10 years. In fact, it has fallen. The average Canadian is worse off than a decade ago, while the average American is earning more. In other words, Canadian productivity has been flat, while American productivity has increased substantially. This opening gap between Canadian and US workers could be called the “jaws of death” for the Canadian economy, as it eats away at Canadian living standards and quality of life.

This means that Canada was falling substantially behind the US even before Trump’s second term, the trade woes, and the spike in global uncertainty. How has Canada fallen so far behind?

Canada has many strengths. Its population is highly educated, healthy, and it is known for a generally high quality of life. It has natural resource wealth and a strong international reputation. There is no evidence that Canadian’s are lazy or less capable. So, why is their productivity falling compared to workers in other developed countries?

The Core Problem: Investment and Talent are Going Elsewhere

A close look at the data reveals the problem: Private sector investment has plummeted, while top talent looks elsewhere for jobs. Smart people and smart money are mobile, and increasingly, they are looking to other markets where the returns on their hard work, innovation, and risk-taking are higher.

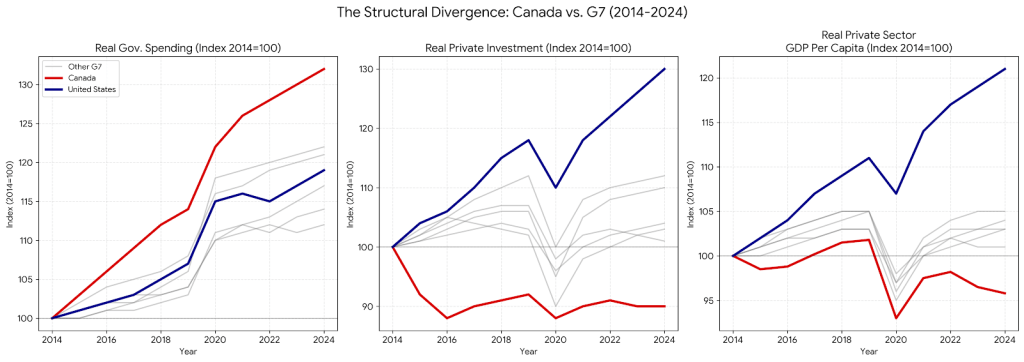

Indeed, when we focus only on the strength of the private economy, removing government expenditures from the GDP calculations, the performance of the Canadian economy since 2014 looks even worse than the total GDP numbers suggest. Figure 2 shows how government spending, private-sector investment, and real private-sector GDP per capita have changed since 2014 in Canada and the other G7 countries, including the US.

Compared to any other G7 country, Canada has had a more substantial increase in government spending, decline in private sector investment, and contraction in economic activity per capita not directly from government expenditures.

This productivity and investment crisis is compounded by a talent crisis. We are witnessing a phenomenon that the Institute for Canadian Citizenship describes as ‘The Leaky Bucket.’ According to their November 2025 report, Canada is hemorrhaging high-skilled talent at an accelerating rate. The study highlights a disturbing rise in ‘onward migration,’ where highly skilled immigrants, having navigated our points system and settled here, are choosing to leave Canada within five to ten years. They are finding that the ‘Canadian Deal’ of lower wages and higher taxes (at least compared to the U.S.) in exchange for a higher quality of life may not longer hold given the costs of living, housing shortages, and increasingly strained health care, education, justice, and social systems.

But the leak is not limited to newcomers. Canada’s most productive homegrown innovators and workers are also increasingly moving to the United States, where skilled engineers, doctors, managers, and entrepreneurs can expect higher compensation and lower taxes. Data from our top engineering schools paints a stark picture: upwards of 60% of software engineering graduates from top programs leave for the U.S. immediately upon graduation.

This is a massive subsidy from the Canadian taxpayer to the American economy. Canada funds education and healthcare for two decades, only to have the many productive workers’ peak productive years, their tax revenue, and their intellectual property accrue to California, Texas, or New York. Canada is effectively training the competition’s workforce.

The result is a Canadian demographic profile that is older, less dynamic, and less productive. Meanwhile, the highly productive doctors, engineers, entrepreneurs, and scientists who do remain feel increasingly squeezed. They face a tax burden that penalizes extra effort and a cost of living that erodes their purchasing power. When success is taxed heavily, but the services those taxes are supposed to fund (healthcare, infrastructure) are visibly declining, the social contract begins to fray.

Addressing the Structural Issues

This means that addressing Canada’s economic woes requires more than just outlasting Trump’s trade threats. It requires a fundamental reset of the domestic environment to reverse the flow of capital and talent. To close the productivity gap, we must dismantle the three structural barriers currently holding the economy back:

1. The Return-on-Investment Problem: Currently, Canada systematically lowers the ceiling on investment returns through tax complexity and high marginal tax rates that kick in at relatively modest income levels. We have created an environment where starting a business is possible, but scaling one into a global competitor is financially unattractive compared to our peers. Capital is mobile; investors allocate resources where the risk-adjusted return is highest. To fix this, we need a compehensive tax overhaul that shifts the focus from redistributing wealth to generating it. If the after-tax return on a factory or startup remains significantly lower in Toronto than in Austin, no amount of government rhetoric will bring that capital back.

2. The Policy Environment and Governance Problem: Major capital investments from mines to manufacturing plants require 10 to 20-year horizons to pay off. Yet, Canada suffers from chronic policy instability, in which the calculus behind any investment can change substantially with the next federal or provincial election or court decision. This political volatility, combined with consultation and permitting timelines that have expanded to the point of paralysis, creates a substantial “risk premium” on Canadian projects. We need to increase approval speed and reduce policy uncertainty. Governments must restore confidence by prioritizing regulatory certainty and implementing strict “shot clocks” for project approval. We cannot build a modern economy if investors fear the rules will change halfway through the decade it takes to break ground.

3. The Quality of Life and Talent Problem: For decades, Canada relied on a “social contract” where lower wages were offset by a superior, affordable quality of life. That value proposition has collapsed. The skyrocketing cost of living, particularly housing, combined with straining public services, especially healthcare, and increasing crime, means that high-skilled workers are increasingly concluding that they are worse off in Canada than elsewhere. Canada must restore its quality-of-life advantage. We can no longer assume that top talent will accept a discount to live in Canada when housing is unattainable, and services are declining. Retaining our best minds requires solving the housing supply crises and ensuring that our high tax burden actually delivers high-quality services. If the math doesn’t work for our doctors, engineers, and innovators, they will continue to live and work elsewhere.

Until we fix this foundation, the gap between Canada and the US will continue to widen, and Canadians will keep falling behind.